The Chariot Race

A few words on The Chariot Race by Alexander von Wagner taking in: Ben-Hur, Gladiator, MacMillan’s Class Pictures from 1932, Victorian-era paintings, The Lady of Shallot, the Empire Marketing Board, Margaret Clarke, how memory plays tricks on us and why “the pig is the great friend of the Irish peasant.”

The Chariot Race by Alexander von Wagner (1838–1919). Photograph by Paul McDermott taken at Manchester Art Gallery.

In a previous post (Bill Drummond’s The Man) I wrote about The Wild Swans and their intended use of a reproduction of The Lament for Icarus, a painting by Herbert James Draper, for their 1982 Zoo 12” ‘Revolutionary Spirit’. The sleeve was withdrawn when permission to reproduce the painting was denied.

MacMillan’s Class Pictures and Reference Book (1932, MacMillan and Co. Ltd, St. Martin’s Street, London). Photograph by Paul McDermott.

Draper’s painting is from 1898 and depicts the dead Icarus, surrounded by lamenting nymphs. It’s a painting I’m familiar with because it’s included in a set of classroom plates that belonged to my grandfather.

In the mid-1930s my grandfather graduated from teacher-training college and started his first teaching position in Watergrasshill NS, Co. Cork. As a graduation present he was given a copy of MacMillan’s Class Pictures and Reference Book, and Teaching in Practice for Juniors a four volume collection of classroom books accompanied by a set of 180 A3 plates and a small reference book detailing information about the pictures on the plates. The MacMillan’s set was first published in 1932 and reprinted in 1933 and 1934. The A3 plates were used by teachers in the classroom as visual aids.

Plate 164: The Lament For Icarus. From the picture by Herbert J. Draper. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

As a child I was absolutely fascinated with this set of plates. We would spent hours poring over the collection and my grandfather would read us the accompanying stories in the books. The collection has ultimately passed to me. The 180 plates are divided into four categories:

Plates 1 - 65: History

These plates start with illustrations of Aborigines Making Fire and Cave-man. Ancient Egypt and Greece, the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages are represented. There are beautiful illustrations of the Wooden Horse of Troy, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, Hannibal Crossing the Rhone, Viking ships, Crusaders, Joan of Arc, Columbus crossing the Atlantic and the departure of the Mayflower from, Plymouth.

Plates 66 - 147: Geography

Given its 1932 publication it’s not surprising that a lot of the geography plates illustrate scenes from around the British Empire. There are Plates devoted to winter sports in Canada, grain crops in Sudan, sheep raising in New Zealand, grape harvesting in South Africa, rice planting in India, tea picking in Ceylon, breaking cocoa pods in Trinidad, a camel train in North Africa. Even the “Irish Free State” is represented (more on this below). The version of history as presented on these plates is from the point of view of Britain, the great colonial power.

Plates 148 - 172: Literature

These are the most beautiful plates in the collection. 24 reproductions of Victorian era paintings. Mostly in black and white with a few reproductions in colour. I’ve been looking at these plates since I was a child. I know every detail of every picture. The greatest pleasure has been stumbling across reproductions of these pictures online (or on a few occasions seeing the original in a gallery) and seeing the b&w plates I grew up with brought to life in their original colour.

Plates 173 - 180: Thirty-two drawings in colour to illustrate Art lessons

These eight plates are double-sided and they illustrate drawing techniques, cut-out patterns, shapes, various objects and colour pallettes.

Herbert James Draper, The Lament for Icarus, 1898

The reference book notes that Draper’s picture: “Illustrates the famous old Greek story of the flight of Dedalus with his son Icarus. Dedalus, the clever artist and builder, who had designed the maze in which the king of Crete kept the fierce Minotaur, made for himself and his son some wonderful wings. They were fashioned of eagles’ feathers bound together with wax. Dedalus had incurred the wrath of the king of Crete by neglecting his work, and he and his son were forced to literally fly from the country with the aid of those wings. As they sped over the sea, the young Icarus, becoming ever bold, flew too near the sun and was drowned before his father’s eyes. His body was washed up on an island where nymphs found him, and sang sweet dirges for him. The island on which Icarus was found was ever after called Icaria, and the sea the Icarian sea.”

Growing up in the 70s my grandfather would tell me these Greek legends and I’d stare at the accompanying plates.

By then he’d been using the plates to bring these stories to life for over 40 years. The plates were passed around his classroom for decades, they were then given to my mother who used them in her classroom for decades more. Some of them have tiny holes in the corners where they were pinned to blackboards. Some of them have stains, creased corners and small rips, but they survived.

How did they survive? They were treasured.

On a recent trip to Manchester I was reminded once more of MacMillan’s Class Pictures. In Manchester Art Gallery I was confronted with The Chariot Race by Alexander von Wagner (1838–1919). It’s a huge painting, it’s roughly 4.5 feet by 12 feet. It takes up nearly one whole wall and as you walk into the room it is incredibly dramatic. I stood frozen. Staring at it for minutes. Taking it all in.

“It’s one of Granda’s pictures,” I thought to myself.

Except of course it wasn’t.

Not exactly.

In fact, not at all.

Memory can play tricks on us.

Plate 32: Roman Chariot Race. Illustration by J. Macfarlane. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

Plate 32 of the set is titled Roman Chariot Race. It’s an illustration by the artist J. Macfarlane. A celebrated illustrator and artist, Macfarlane was born in 1857 in Bonhill, Scotland and immigrated to Australia in the 1880s. Macfarlane’s Roman Chariot Race is obviously his recreation of von Wagner’s The Chariot Race.

Presumably MacMillan didn’t have permission to reproduce von Wagner’s painting and hired Macfarlane to recreate a version of it. Macfarlane contributes nearly 40 illustrations to the MacMillan set of plates.

Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ was published in 1880 and von Wagner’s The Chariot Race is thought to be from 1882. Some have suggested that von Wagnor was inspired by Wallace’s novel and others have written that Wallace may have been inspired by earlier versions of the painting by von Wagnor.

A 1901 poster for the theatre production of Ben-Hur.

What is not in doubt is that when Ben-Hur was adapted into a stage production in 1901 by the famed theatre producers Marc Klaw and Abraham Erlanger they used a version of von Wagner’s The Chariot Race to promote their stage show. When this production toured Europe audiences were told that the chariot race sequence in the stage production would “realise” von Wagner’s painting.

Von Wagnor’s The Chariot Race had an obvious influence on William Wyler’s 1959 Ben-Hur, which in turn influenced Ridley Scott’s later depictions of a chariot scene in Gladiator.

“The pig is the great friend of the Irish peasant.”

Plate 136: Irish Free State Farm. Reproduction of an Empire Marketing Board Poster illustrated by Margaret Clarke. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

Plate 136 (pictured above) is one of two reproductions of illustrations in the set by the celebrated Irish artist and illustrator Margaret Clarke. Irish Free State Farm was one of five posters that Clarke illustrated for the Empire Marketing Board (EMB), a British government department in the late 20s that encouraged the British population to buy goods from “the Empire”.

The accompanying reference book contains the following description: “In Ireland co-operative marketing has been of great help to dairy farming. Each morning the farmer takes his milk to the nearest creamery, where the cream is separated from the milk. The farmer is paid for the cream; the skim milk he takes home for the use of his family and pigs. In dairy farming districts, those with quick transport to market produce fresh milk, and those farther away turn the milk into butter, cheese and dried milk products. The markets for these goods are the great manufacturing areas of the British Isles. In all daiy districts pigs are reared. They use up waste products, since they are fed on the skim milk and the whey, and the profit made on their sale adds to the farmer’s income. England and Wales have about 2 1/2 million pigs, Ireland 1 1/2 million and Scotland about 140,000. Ireland is noted for its bacon and the pig is the great friend of the Irish peasant.”

Margaret Clarke, The Irish Farm, Empire Marketing Board Poster.

Plate 70: Coal Mine in the United Kingdom. Illustrated by Margaret Clarke. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

The “Harry and Margaret Clarke Papers” collection is in The National Library of Ireland and Margaret Clarke’s work for the Empire Marketing Board is explored in detail on the NLI’s website here.

Margaret Clarke, Coal Mining.

In total Clarke illustrated five posters for the EMB. Four illustrated goods imported to Britain from the Irish Free State and one (reproduced above) illustrated coal exports from Britain to Ireland.

Plate 76: Timber Stacking in Burma. Reproduction of an Empire Marketing Board Poster illustrated by Ba Nyan. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

Timber Stacking in Burma is another reproduction of a vintage poster issued by the EMB. Ba Nyan was a Burmese artist who studied at the Royal College of Art in London in the 1920s.

The accompanying reference book contains the following description: “Elephants are used in the teak forests of Burma for piling logs. The elephant in the picture has a native boy on his back, a mahout, to guide him in his work. The boy site on a saddle harnessed to the elephant with ropes, which pass around its body and neck. The sky is bright, and the boy wears a turban to protect him from the hot sun. There are palm trees in the picture, and white houses bathed in sunlight. Beyone rises a tall factory chimney.”

Ba Nyan, Timber Stacking, Empire Marketing Board Poster.

Plate 116: The Empire’s Sugar Cane. Reproduction of an Empire Marketing Board Poster illustrated by Elijah Albert Cox. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

Elijah Albert Cox was a painter and illustrator, born in London. The Empire Sugar Cane plate reproduces another EMB poster from the late 1920s.

The accompanying reference book contains another jarring colonial description: “In this picture coloured men are carrying away to the mill bundles of sugar cane which have just been reaped on the plantation. At the mill the canes will be crushed in a machine which has heavy rollers, and the sweet juice of the canes will be squeezed out. The sun shines fiercely down on the men, who have water in stone pots for drinking.”

Elijah Albert Cox, The Empire’s Sugar Cane, Empire Marketing Board Poster.

MacMillan’s Class Pictures has 24 plates of reproductions of Victorian-era paintings and these were used to illustrate works of literature in the accompanying books.

Plate 164: The Finding of the Infant Moses. From the picture by Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

One of my favourite plates is No. 164, The Finding of the Infant Moses by Anglo-Dutch artist Lawrence Alma-Tadema, from 1904. It is rumoured that his works fell so far from favour that in the 1950s this painting was sold for its frame. It was eventually sold to a private collector at auction in 2010 for nearly $36 million.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, The Finding of Moses.

The reference book notes: “In this picture Pharaoh’s daughter, carried in a litter by Nubian slaves, is gazily happily at the infant Moses who is bourne in the ark of rushes by the princess’s handmaidens. On the opposite banks of the Nile can be seen the toiling Israelites, the wretched slaves of Pharaoh.”

Plate 170: Sir Isumbras at the Ford. From the picture by John Everett Millais. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

A Dream of the Past: Sir Isumbras at the Ford by John Everett Millais depicts a medieval knight helping two young children over a river. This was always my mother’s favourite plate from the set. She never told me why she loved it, but we guessed it was because it reminded her of her own childhood and her relationship with her only sibling, my uncle Matt, and her dad, my grandfather.

Years ago I got the plate of Sir Isumbras at the Ford framed for her. When she unwrapped the picture she cried. It held pride of place in her “good room”.

The reference book notes: “The picture illustrates one of the Early English Metrical Romances, written probably in the early half of the 14th century. Sir Isumbras was a famous and wealthy knight who fell into the sin of pride and was warned by an angel of his impending punishment. He was stripped of his possessions and his castle was burned to the ground. His wife and three children were forced to beg for any clothes that their neighbours could spare, and the family then set out on their one horse on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to expiate the knight’s sin. Soon after they started they came to a wide shallow river, which barred their way. Sir Isumbras carried the two eldest children across the ford on his horse, and left them on the opposite side while he returned to fetch his wife and youngest son. While the knight was gone, a lion carried off one child and a leopard the other. Soon after, his lady wad stolen by the Saracens, and his youngest son was carried off by a unicorn. After a series of further misadventures by which the knight was thoroughly humbled, the several members of his family were miraculously reunited, and lived in prosperity for the rest of their days.”

John Everett Millais, A Dream of the Past: Sir Isumbras at the Ford.

We got other plates framed too, pictures that held special meaning to myself and my siblings. But it meant that my original set of plates was incomplete.

A few years ago while researching the set I came across a listing online. A complete set was for sale, I couldn’t believe my luck. I picked it up for a steal. The second set also came with the Reference Book. The original Reference Book from my grandfather’s set had been badly damaged in a school fire in the 1980s. Unless you knew what exactly the set was it would have meant nothing to the average person, but of course it held special meaning for me. I lucked out, I now have two sets - one complete set and loads more plates to eventually get framed for my sons.

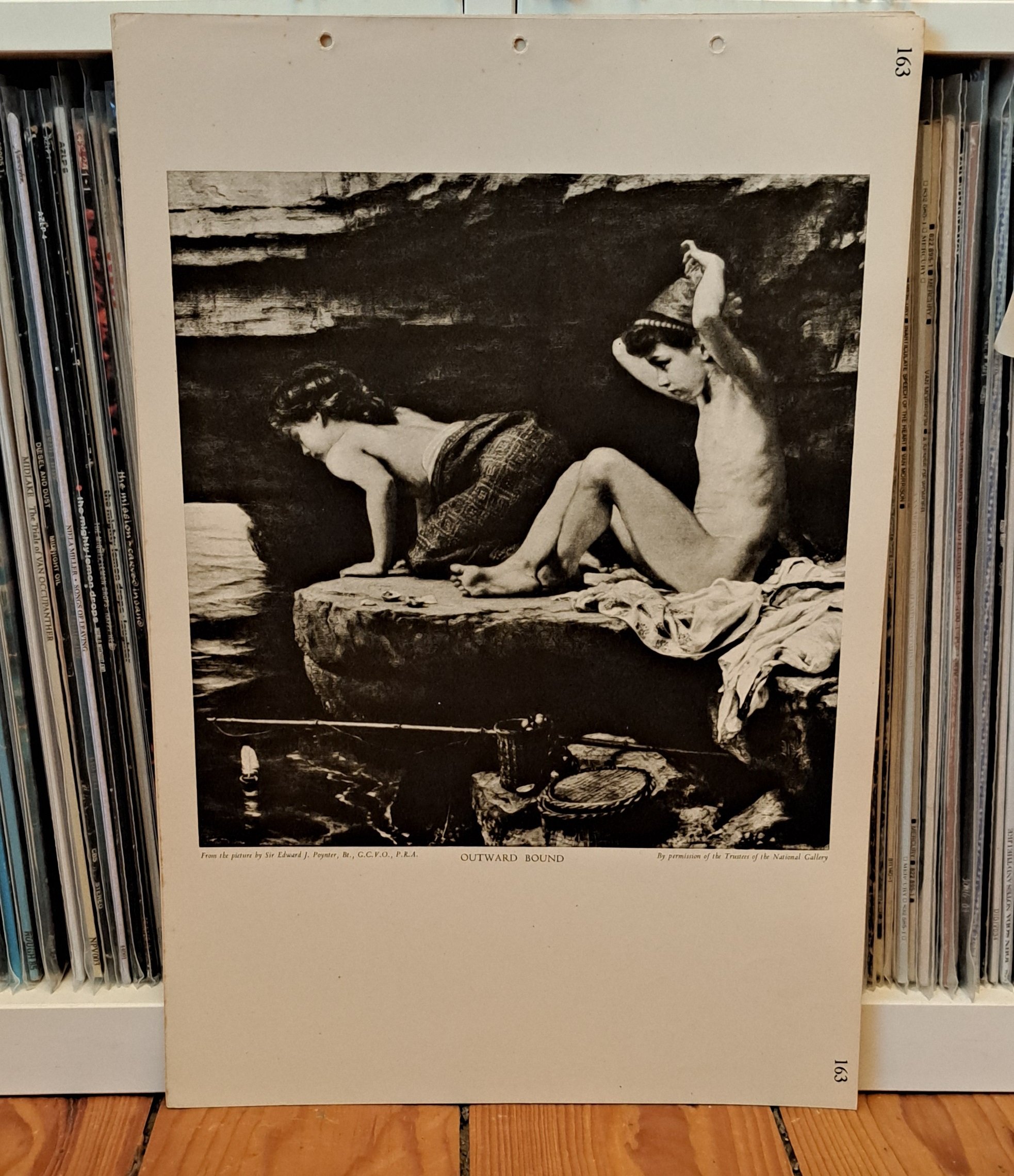

Plate 163: Outward Bound. From the picture by Edward John Poynter. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

Poynter’s Outward Bound is another favourite plate from my childhood and another plate that I had framed.

The reference book notes: “This charming picture shows an idyll be the sea. Two little girls have made from a walnut shell and a feather, a toy ship which is sailing under a rocky archway, “outward bound” for the sea beyond.The fishing rod, the basket of bait, the second basket which probably contains food, the rocky cave, the cockle shells, all offer material for discussion in class.”

Edward John Poynter, Outward Bound.

Plate 162: Faithful Unto Death. From the picture by Edward John Poynter. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

Outward Bound isn’t the only Edward John Poynter picture in the set. Faithful Until Death is probably his most famous work.

The reference book notes that: “Before studying this picture, the children should be given a brief description of the destruction of Pompeii.” The note is a reminder that the 180 MacMillan’s Class Pictures and the corresponding Reference Book, and four volumes of Teaching in Practice for Juniors were published as classroom aids. The teacher would read the story from one of the volumes of books, find the corresponding plate to hold up to the school children or pass around the classroom and then read out the entry in the Reference Book.

When Pompeii was excavated in the early 19th century, the skeleton of a soldier in full armour was discovered. Romantic historians assumed that he had remained loyally at his post while all the others fleed from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Edward John Poynter, Faithful Unto Death.

The reference book explains that: “The picture portrays a scene in one of the Roman cities at the time of the eruption of Vesuvius. An archway is shown, under which stands a Roman soldier whose duty it is to guard the gate. Beyond the gate can be seen panic-stricken people seeking escape from the city. A man and woman stand paralysed with fear of fiery lava which is falling on them. The darkness of the scene is illuminated by the glow of the volcano, which lights up the resolute and calm countenance of the faithful soldier, who remains at his post in the doomed city.”

Plate 148: Ulysses and the Sirens. From the picture by John William Waterhouse. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

Ulysses and the Sirens is by the Pre-Raphaelite artist John William Waterhouse. It depicts a one of the adventures of Ulysses told in the Odyssey.

John William Waterhouse, Ulysses and the Sirens.

The reference book notes: “On his homeward journey after the fall of Troy, Ulysses encountered the Sirens, the beautiful nymphs whose songs lured sailors to land on an island where they met destruction. Being warned beforehand of their powers, Ulysses prepared to frustrate the Sirens by stopping the ears of his sailors with wax. Himself he ordered to be bound to the mast so that the may hear their songs and yet be unable to respond to their charms. In this way he and his crew passed the Sirens in safety. The artist has represented the baleful Sirens as feathered birds with women’s heads, circling round the Greek galley which is rowed by sailors having their ears bound. Ulysses, in Greek costume, stands tied to the mast.”

Plate 157: The Sleeping Beauty. From the picture by Edward Burne-Jones. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

This has always been my favourite plate in the collection. My mother got it framed for me decades ago.

The reference book notes: “This representation of the famous old fairy story is a delightful example of Sir Edward Burne-Jones’ detailed decorative style. The princess is shown lying on a couch surrounded by her four maids of honour. The children should notice the embroidered pillow and coverlet, the rich hangings of the bed, over the head of which hangs a lamp with a handsome circular frame. The four ladies lie asleep on the floor, where they had been sitting on cushions. One holds a lute, another has let fall a comb and mirror. On the left of the picture stands a carved jewel casket, out of which a jewelled crown has been taken. The room is festooned with branches of flowering wild rose, which twine about the walls and bed, and blossom even among the jewels of the crown.”

Edward Burne-Jones, The Sleeping Beauty.

The Lady of Shalott is another painting by John William Waterhouse in the set. It is a representation of the ending of Alfred Tennyson’s 1832 poem of the same name. This is one of only a few plates in the set that is printed in colour.

Plate 167: The Lady of Shalott. From the picture by John William Waterhouse. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

The reference book notes: “This picture illustrates the well-known story of The Lady of Shallott as told in Tennyson’s poem. It is highly decorative in style, rich and colourful. The lady has apparently just entered the boat, for she holds in her right hand the chain by which she has loosened the bark from its moorings. She sits in a richly-embroidered cloth; at the prow of the boat hangs a lighted lantern, for it is evening.”

John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott.

As I was putting this post together I coincidentally came across Miriam Ingram’s song ‘The Lady of Shallot’. Ingram is an experimental singer/songwriter from Dublin, “who entwines acoustic and electric elements to create music that is both delicate and bold.” Earlier this year she put Alfred Tennyson’s poem, ‘The Lady of Shalott’ to music. It can be heard below: