Gavin Friday (in his own words)

“WE DID IT BECAUSE IT WAS THE REVOLUTION IN OUR HEADS.”

an oral history by Paul McDermott

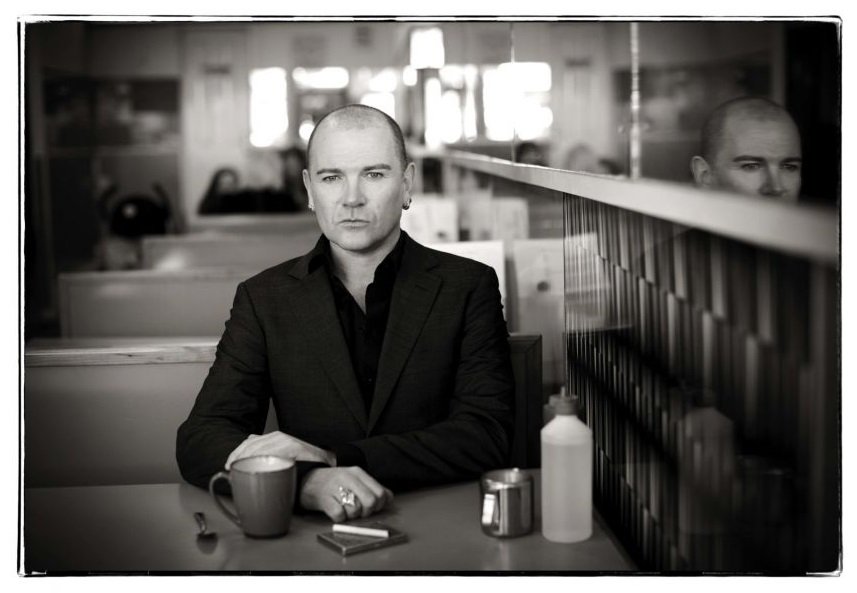

Gavin Friday. Photograph by Peter Rowen, used with permission.

My name is Gavin Friday. I’m — let’s say — a former Virgin Prune. I formed the Virgin Prunes in 1977 in Dublin and since those days have still been and still am involved in music, the Arts and God knows what else.

Introduction

I interviewed Gavin Friday in March 2019. He had agreed to contribute to my radio documentary No Journeys End — the story of Michael O’Shea and I also wanted to talk to him for liner notes I was writing for Hiding From the Landlord the compilation of Finbarr Donnelly and his bands Nun Attax/Five Go Down to the Sea?/Beethoven.

Listen to the full Gavin Friday interview below:

Songs To Learn And Sing – EP 768

Gavin Friday on the early days of the Virgin Prunes, the influence of David Bowie, Dublin's Project Arts Centre, post-punk philosophies, The Fall, Vox magazine, Michael O'Shea, Five Go Down to the Sea?'s Finbarr Donnelly, PIL, the NME's C81 cassette, My Bloody Valentine, Cathal Coughlan, and London.

Our conversation on the day jumped all over the place but central to the chat was the concept of outsiders in music and the gravitational pull of London in the late 70s and early 80s. Gavin touched on the early days of the Virgin Prunes, spending a lot of their Rough Trade album advance on photographs in the Wicklow mountains, the influence of David Bowie, Dublin’s Project Arts Centre, post-punk philosophies, The Fall, Vox magazine, Michael O’Shea, Five Go Down to the Sea?’s Finbarr Donnelly, PIL, the NME’s C81 cassette, My Bloody Valentine, Cathal Coughlan, and London.

Virgin Prunes: A New Form of Beauty (compiles 7", 10", 12" and Cassette formats of A New Form of Beauty, originally released by Rough Trade in 1981), Heresie (originally released as a double 10" record by L’Invitation Au Suicide in 1982), …If I Die, I Die (originally released by Rough Trade in 1982), The Moon Looked Down And Laughed (originally released by Baby Records in 1986) and Over the Rainbow (A Compilation Of Rarities 1980–1984). All reissued by Mute in 2004. Images from Discogs.

When I asked Gavin to introduce himself he gave me a wry smile and said, “I’m a former Virgin Prune. I formed the Virgin Prunes in 1977 in Dublin and since those days have still been and still am involved in music, the Arts and God knows what else.” The Virgin Prunes lasted from 1977 until 1986 and released two full length albums — …If I Die, I Die (Rough Trade, 1982) and The Moon Looked Down and Laughed (Baby, 1986) — as well as countless singles and EPs. In their early days the band abandoned traditional rock & roll tropes in favour of performance art, installations and the avant-garde. Early gigs were often staged in performance spaces and galleries rather than pubs and clubs. Their live shows were legendary confrontational events: audiences were often simultaneously shocked and bemused, as the hilarious Twitter exchange below testifies:

The band left Dublin for London in 1979 and spent the next few years gigging throughout Europe where they enjoyed a huge following. The band decamped to Berlin and was fêted in France, Holland, Belgium and Germany. The UK music press of the day either loved or hated the band. Articles about the band were either positive or downright negative — indeed many were vitriolic, caustic and simply nasty. In order to add context to what Gavin discusses I’ve peppered this feature with some quotations from various reviews and interviews published between 1982 and 1983 in both the NME and Melody Maker.

After the break-up of the band Gavin went on to forge an idiosyncratic solo career that to date has seen him release four solo records as well as countless soundtracks and other works. When I sat down to chat to him it was in the studio where he was working on a new record — a record which will hopefully be released sometime soon.

What follows is Gavin Friday in his own words…

Note: This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and timeline purposes.

Gavin Friday: Each Man Kills the Thing He Loves (with the Man Seezer) (Island Records, 1989), Adam ’N’ Eve (Island Records, 1992), Shag Tobacco (Island Records, 1995) and Catholic (Rubyworks, 2011). Images from Discogs.

The Virgin Prunes are Irish. This has got nothing whatsoever to do with the comically inept state of their performance art, but it might explain the presence of a partisan audience largely consisting of Irish exiles prepared to put up with their nonsense. Or maybe there’s something about the Virgin Prunes that reminds them of a wake.

Chris Boyn — NME, 23 January 1982

Usually when you’re about 19, 20, 21 you shoot yourself in the foot constantly, you’re just not that articulate. There’s something quite nice about that.

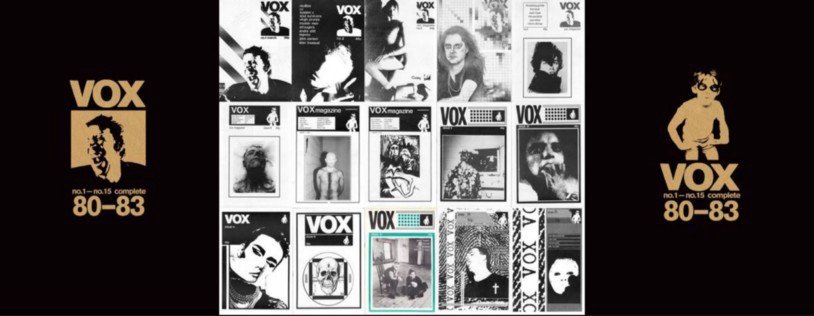

I have very fond memories of Vox. Numerous fanzines came and went really quickly in the late-70s early 80s. Vox came in the early 80s but was very different in that in that the man [Dave Clifford] was quite driven. He wanted it to be very much about the alternative. He wasn’t that interested in talking about The Undertones, who were quite commercial in 1980. The word post-punk is interpreted in many ways but he wanted that other world away from The Sex Pistols and The Clash. He was into — it’s a word that is used a lot now in the last few years — the outsider and the bespoke.

Vox №13–1982.

What was wonderful about him was it didn’t come out once a month it came out whenever it was ready. He’d come up to Dublin and he’d hang about and go to gigs. You’d meet him in town and you’d sit down and he’d talk about albums or films we saw. Without interviewing you he was almost like reviewing you or enquiring about where your brain’s at and then he would do an interview.

There was an incredible elegance about Dave Clifford, but the ego was left at home, which is a really rare thing. The fanzine, which was a thing in those days, had a lead singer about it, it had an ego about it, a personality. This guy, his aesthetic came from performance art and minimalism and modernism. Even graphically everything was stripped away to something very clean and he didn’t edit you interviews. Usually when you’re about 19, 20, 21 you shoot yourself in the foot constantly, you’re just not that articulate.

Dave Clifford’s Vox magazine — 15 issues were published between 1980 and 1983. All 15 issues were re-published in a collection in 2019 by HiTone books.

There’s something quite nice about that. I bought the 40th edition and I read back some of the stuff and what I found was an energy and enthusiasm of the young voices and the attitude — an incredible amount of attitude.

What the Prunes actually attempt to do on stage and through the records is actually hard to describe, simply because they have no peers or convenient reference points within the relatively conventional rock-pop scenario. Ian Pye — Melody Maker, 27 March 1982

How did I fuckin’ know that?

Who likes listening to their own voice? If you play this [points to recorder] back you vomit usually. Who likes reading what they wrote when they were 15, 16 or 17? But sometimes I’m quite amazed, like there’s certain things in my Virgin Prune work and I think how did I fuckin’ know that? When I was 18 I wrote some quite profound lyrics and quite profound stuff and that intrigues me. We worked and wrote really quickly, which is something really enviable as you get older, as we over analyse.

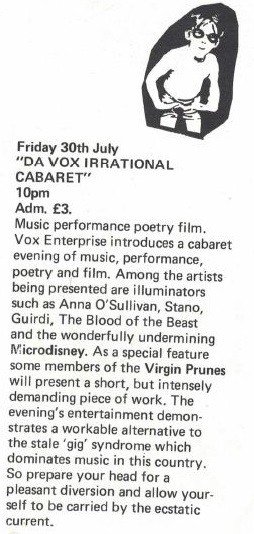

The Irrational Cabaret

(Friday 30 July, 1982).

Image from John Byrne.

So yes, I did smile reading Vox again, I did sort of go, that’s interesting. It was so over the top as well but quite beautifully. I sorta go, wow where are the bands like this now? Maybe they’re hidden but I can’t hear them.

A lot of memories. At the early days of the Virgin Prunes we didn’t know how to play our instruments and myself and Guggi were very visual. We both painted, we both found a home in the Project Arts Centre very early on, around 1976. We started sticking our heads in there before we even formed the band. Seeing Nigel Rolfe doing his performance art and his installations we were quite intrigued, so much so that we almost saw it as the DIY philosophy in punk rock. We said, “Why can’t we bring that into our show, visually do that?”

Vox Enterprise Presents — The Irrational Cabaret at the Project Arts Centre (Friday 30 July, 1982).

Image from John Byrne.

A typical Prunes performance or record — not that there’s any such thing as a typical performance or record — can test your tolerance level like nothing else. Paul Du Noyer — NME, 3 July 1982

Bowie — he was fuckin’ hugely influential to all of us kids.

A lot of punk or post-punk bands they come from an almost conceptual marriage of Sex Pistols and Bowie. The visceral attitude of punk and DIY but the theatrics of Bowie — the out-there-ness, the confrontational but also the fact that Bowie was going to different places from the glam rock — Diamond Dogs is probably the first punk album — to soul but then really interestingly as punk was going off he went to Berlin and embraced avant-garde music and electronics. I remember Low, all those wordless vocals, he was fuckin’ hugely influential to all of us kids. We saw this playground of the Project that we could do what we wanted and they let us do what we wanted. So we started doing small shows.

Vox No.1-No.15, 80–83 (HiTone books, 2019). Photographs by Paul McDermott.

We did a show in 1980 called the One Shows. But it was actually four shows a night. The night before we wrote the music, played it once, never played it again and then the next night we were improvising, we didn’t have video tapes but we had TVs, we were playing with reel-to-reels, we were doing all this stuff that all these avant-gardists and these other people were reading about, but we had a platform within the Project Arts Centre to do what you want. You didn’t have the pub-rock buying punter that was in the Baggot Inn or in McGonagles.

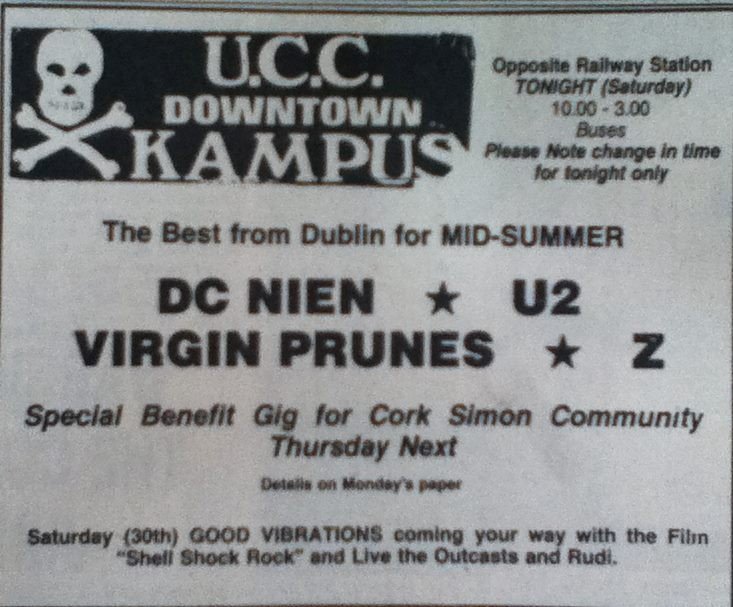

We really went there. Our second or third gig was more to do with performance art or installation than it had to do with music. But we had to get out — that’s the real truth. We went to Cork once. That was quite interesting because that was the first time I met Cathal [Cathal Coughlan — Microdisney] and the first time that I met Donnelly [Finbarr Donnelly — Nun Attax]. They’d heard of the Virgin Prunes and there was a great kinship but we were a little bit more fuckin’ out there and we had already jumped into Europe. We got really rejected quickly from Dublin and it was difficult for us in Dublin. So we said, “Fuck Dublin!” London became our home for a while but we got out of there really quickly too.

Virgin Prunes — Downtown Kampus at the Arcadia, 23 June 1979. Image taken from Elvera Butler’s Facebook photo album REEKUS GIGS.

The first time I saw the Prunes I couldn’t tell if their vocalists were male or female, because of their dresses and the bad lighting; but the lighting was bright this time and I managed to see how ugly they are.

Caroline Harper, Melody Maker, 6 November 1982

You wanted to embrace the outsiders.

I met Vox around ’81, ’82 when Europe was really becoming more of our home than London. London to me was extraordinary in the punk days. I first went to London in ’76 as a 16 year old boy to see David Bowie do Station to Station live. I slept in a train station and got the train boat back. This is in the days before the fuckin’ IRA campaign got too heavy so train station sleeping stopped in the early 80s. In ’78 I saw Bowie again but punk had kicked in. London had the inspiration and the fire and the record shops and the gigs — you were seeing everyone from The Fall to Wire — Wire become a huge big influence on me — and Joy Division and all of this. London was just this extraordinary, extraordinary place.

The bible of punk/DIY was very much in our blood stream so you could not sign to a major label you had to go work with Factory or Rough Trade. You could not bring in an ordinary producer, you had to bring in an artist. We were all running on those very beautiful theories — sometimes they’re right and sometimes they’re wrong. But at the end of the day it’s what the WORK is. It was in this mayhem of hanging out in Rough Trade in Ladbroke Grove. The Virgin Prunes used to wear dresses — but we were banned from entering Rough Trade because of how we dressed, that’s how liberal liberal can get with Rough Trade. We were banned from playing a lot of places in Dublin because of that. We had to do all our meetings in a pub. Everything was very political, even if it wasn’t politics it was very earnest, very intense. It was that time that you were looking for the awkward, you were looking for the extraordinary. You wanted to embrace the outsiders. It’s where I met incredible people.

It’s where I first met Wire, and Graham — Dome, which was a sub-group of Wire. It wasn’t that we were just fans of them and their music. They were people that would sit down in the pub and talk: “Did you see that performance art?” “Have you come to the Project Arts Centre?” “Have you heard of Nigel Rolfe?” “Have you heard of Neu! this band from Germany.” It was like that, we weren’t really interested in the Pretenders or Siouxsie and the Banshees — it was much more the awkward things. It was then that this character of Michael O’Shea came up in conversation.

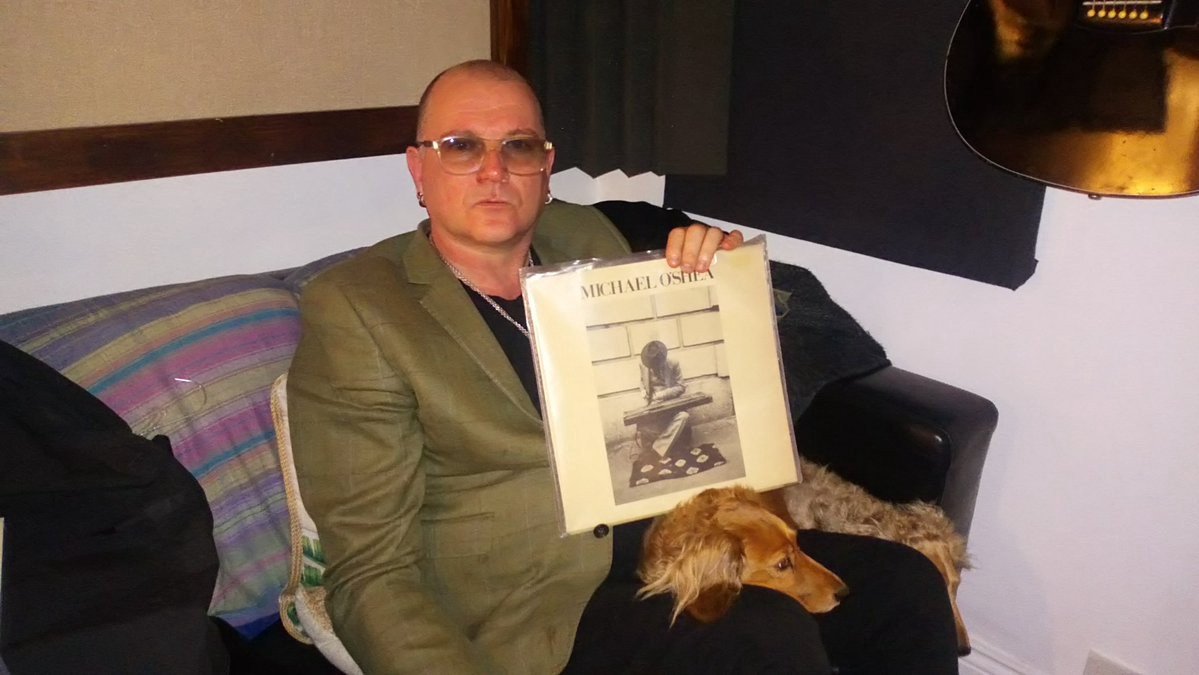

Michael O’Shea. Photograph by Graham Lewis

I had seen him busking, near Tube stations usually, but what was extraordinary about this was that he always reminded me of Bowie in the last scene from The Man Who Fell to Earth. Bowie has the big hat and the suit and he drops his head. Obviously he’s turned into this doomed alcoholic, it just ends with the head dropped and this stylish man. I’m walking by and I see this hat and this stylish man in a suit sitting on the ground playing this crazy thing. I didn’t know what it was, it was like a xylophone meets a slide guitar, or one of those Country & Western guitars. The sound was psychedelic but Gaelic, a bit of Philip Glass, it was a bit of everything. It was: [Laughing] “What the fuck is that?” It was in Notting Hill where I first saw him. I never went near him at that stage.

I remember sitting with Graham and talking about this guy — “he’s the type of person like, maybe we should get him to work with us as a producer?”

It almost has the same feeling of, though very different to, that amazing recording of ‘Jesus Blood Never Failed Me Yet’ by Gavin Bryars that Eno released in 1975. ‘No Journeys End’ is really evocative and it sounds like it’s always been there and your man always was there and maybe that’s why. I mean how many times had Michael played that piece [‘No Journeys End’] before it was recorded? How long was he out on the streets? I only became aware of him around 1980.

Gavin Friday (with Stan and Ralph), Dublin March 2019. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

I remember Graham trying to get gigs in Dublin for him. But there was no way of contacting the man, you’d either see him out busking or you didn’t know where to find him there was a little bit of the hobo about him. Squats were quite sophisticated in those days, this is just before Thatcherism’s claw ripped the fuck out of everything. A lot of people would live in squats and be happily there for years. There was no phones in those days, even people in flats didn’t have phones, it was public phones. When we met him he’d have been in his mid-30s — which is old in your head, when you’re 20. I was around 20 and I thought he was an old man. I just found him incredibly mysterious, with this dream like magic, I’d never really heard anything like it before or again, I’ve never really seen anyone play those instruments in the way he did.

He’s like a Sci-Fi Trad player. Yeah, that’s a good analogy.

The music is sort of indescribable in the sense that it feels like a one man orchestra. What’s really interesting about it is that it’s got the storytelling that Irish Trad folk people can do. When you get somebody as extraordinary as Martin Hayes — the main guy from The Gloaming, I’m a big fan of Martin’s solo stuff — it’s that sort of mysterious storyteller. People say he’s for the birds, but he is with the birds and he’s bringing the orchestra with him and you with him. Michael has that, in that he’s a solo performer who’s playing. Is it a sitar? Is it a slide guitar? Well what is it? “Mo Chara”, he made it himself! It has this fusion of stuff, the Indian shit brings on the psychedelia but then it has that Celticness as well. He’s like a Sci-Fi Trad player. Yeah, that’s a good analogy, that in the late 70s happened to look like The Man Who Fell to Earth busking [laughing].

It’s incredible the way a lot of these outsiders — which is what in truth they all were — gravitated to London.

Virgin Prunes — ‘Red Nettle’

All the Virgin Prunes contribute is a veneer of mannered primal angst and the portentous mystique of nostalgie de la boue. Mat Snow — NME, 27 November 1982

Let’s get the most avant-garde thing ever, no voices, no rhythm, no guitars, we’ll just loop this mad shit.

We got out of London but we didn’t really come back to Dublin because we kept going away. We started gigging seriously outside of the country from 1979 on. The first time we played London was 1979. We would be in Europe for nine or ten months of the year. If you split that up, we’d be home in Dublin for three weeks at Easter, three weeks at Christmas etc. Just running back. We lived in Berlin for two years at one stage coming back and forth. But we got out of London. London we found quite regressive too. It’s quite interesting, Geoff Travis won’t like me saying this, but suddenly all these incredible bands that were on Rough Trade started selling records and then it went BANG. Every single band was dropped, from Cabaret Voltaire, to the Virgin Prunes to The Fall. The Smiths were there and literally the careers of 20 bands were put on hike. For Morrissey’s daffodils, I used to say. But you know, The Smiths were quite great.

NME/Rough Trade C81 — Various Artists (New Musical Express-Rough Trade Copy 001, 1981). Image from Discogs.

There was a thing that happened in 1980 and it was quite a revolutionary thing — the NME C81, a cassette. It was the first time it ever happened, cassettes were suddenly hip. This was when the NME would sell 250,000 copies a week. Can you believe a newspaper sold a quarter of a million a week? It was extraordinary — the writing alone of one of my heroes Paul Morley, the heyday of Joy Division, The Cure were starting off, the heyday of Bowie, everything just full force — the NME was like a bible and we were on that cassette. We had recorded our first two EPs — I wouldn’t do an album for a year because I was like, “We don’t do albums!” Geoff said, “this is huge, I got Scritti Politti’s ‘Sweetest Girl’ on it, and we’ve got The Raincoats on it.” I actually said to Dik and Binttii, “Let’s get the most avant-garde thing ever, no voices, no rhythm, no guitars, we’ll just loop this mad shit.” It’s called ‘Red Nettle’. It’s fuckin’ great, but Jesus Christ everyone was going, “Why do you do that?” We did it because it was the revolution in our heads. [Laughing] I think Geoff held that against us.

NME / Rough Trade C81 Owner’s Manual — 31 January 1981.

I remember, when it came time to make an album, I didn’t want to work with producers. We made A New Form of Beauty, which was really an album, but we did it as a 7", then a 10", then a 12", then a gig, then a video.

Press adverts for A New Form of Beauty — NME, 12 December, 1981 and The Face, December 1981. Images from nothelseon.

Dave Clifford in Vox did a big thing on this, weighing in to the whole craziness of where we were going. We were taking up philosophies — Bowie’s philosophies, but more Johnny Lydon and Public Images’s philosophies.

Virgin Prunes — A New Form of Beauty (Cassette, 7", 10" and 12" — Rough Trade, 1981). Images from Discogs.

Whereas U2 are cleancut and direct, the Prunes attempt to intrigue and mystify with a shambolic pretence of spontaneity and a clutter of Gothic-horror props. Dismembered dolls, death-mask face-paint, monks’ robes and the scattering of ashes are devices too clichéd to be either shocking or amusing. Like Screaming Lord Sutch, it’s feeble vaudeville.

Mat Snow — NME, 4 December 1982

Making music, sort of for the madness of it, for the sake of it.

Public Image’s first three albums were quite revolutionary. Wire and Throbbing Gristle, all these people were becoming friends. Geoff thought that maybe we should get one of our friends to produce us. At one stage I did mention Michael [O’Shea] and it was just, [laughing] not even on the table. It was just like, “that won’t be happening.” I mentioned Wire and Graham, and he said, “you need more discipline, you can’t have ‘Red Nettle’.” ‘Red Nettle’ was in that zone of Dome. I mentioned Sleazy and Genesis — they had done an album for 23 Skidoo, but it was a little bit hippyish. So we ended up going with Colin Newman.

Virgin Prunes — ‘Baby Turns Blue (Director’s Cut)’ Remix by Colin Newman

I remember we got 10 grand budget, which was a lot — sterling. The stupid thing Geoff did is he put it into our account and we went out and we spent 6 thousand of that on photo shoots [laughing]. We brought in Ursula Stiger — incredible photographs. We spend two weeks doing these photographs, we went out to the forest, to the mountains in Wicklow. We actually lived there for three days, we went all primeval and photographed it. Geoff said, “do you realise that you spent more than 50% of your recording budget?” He said, “Bowie doesn’t spent that much!” We said, “Exactly!” [Laughing] But we said, “Let’s make photographs that no one forgets.” [Laughing] You can see how we all demented Geoff and he just wanted something straightforward.

Virgin Prunes — …If I Die, I Die (Rough Trade, 1982). Photographs by Ursula Stiger. Images taken from Discogs.

We took on the idea of Michael O’Shea doing an album with us more for the nuance of where could this go, where could this bring us.

That’s what was incredible about this era, it was making music sort of for the madness of it, for the sake of it and this wasn’t like a drug infused 1969 or 1971 where incredible experiments were happening with psychedelia, this was people who smoked a bit of spliff, people got drunk — that was it. It wasn’t a drug culture between ’78 and ’82, it really wasn’t. I don’t think there’s been a time like it — that era. What I found really extraordinary about that era was when you went to England you had people like Cabaret Voltaire from Sheffield, The Fall were extraordinary — I mean Mark Smith, he was like Samuel Beckett on speed goes punk rock — forceful. I don’t think you are ever going to see that again or experience it. I can’t see the energy in 20 year olds. It looks like the energy is in the 50 and 60 year olds. Are you going to see a new vibrancy from older people? You sorta have in the last 10 or 20 years. The most interesting albums in the last 15 years were probably made by Lou Reed and Bowie before they died — maybe I’m just a fuckin’ romantic, I don’t know.

The Prunes may have discarded some of their intricate and confusing surreal elements (remember the DaDa sitting room, the dead fish, the pig’s heads?), but they’ve lost none of their bite. Gone is the slime, the body paint, the mutant plastic dolls — the Prunes stand naked now (now there’s a thought!) and proud, defying ridicule and scorning disdain. Helen Fitzgerald — Melody Maker, 20 August 1983

I Ioved them. I loved the fuckin’ name — NUN ATTAX.

When I met first Donnelly and Cathal in Cork, they were all on the verge of starting bands. The Virgin Prunes were that little bit earlier than them. They came to see us live and they were back stage. I went to see the Nun Attax play live in McGonagles when they first came to Dublin about a year or so later. I Ioved them. I loved the fucking name — NUN ATTAX. They were similarities, it was just how the fuck can you control that singer? Well you can’t. I was a bit similar, the angst and the adrenaline. The beautiful thing was that we had this medium, this thing called music, this thing of being in a band, to let go of all that angst. I could see that with Donnelly.

Hiding From the Landlord — Nun Attax/Five Go Down to the Sea?/Beethoven (Allchival Records, 2020).

Probably the worst thing in the world for them was London — there’s no repression there but no real care either. There’s a few million other people and it’s usually the insecure, complex guys that get lost. England likes you to be a little bit contrary and funny, ah you’re a mad fucking cunt but you don’t really mean it, you’re funny. I think Donnelly went, will I be this, will I be that, will I be the court jester — I think it was a real struggle for him. I think London killed him but then I didn’t know him that well, I could be wrong.

Ireland’s first transvestite band do a meticulous sweeping-beneath-the-carpet job, accentuating their tacky dramatics and pulling attention away from the ponderous, tolerance testing tripe they actually play. Amrik Ral — NME, 20 August 1983

There was always subliminal racism in England, I really believe that.

I can remember giving advice, I’m not very good at advice because I fucked up a lot, but I can remember talking to My Bloody Valentine and they coming up to me. It was ’83 maybe? “We want to go to London.” I said to Kevin Shields, “don’t fuckin’ go to London, it’s a vampire. They don’t care, you’ll scream, you’ll be killed.” They said, “where’ll we go?” I said, “go to Holland, I’ll give you names, at least you’ll get gigs, at least there’ll be money.” There was always subliminal racism in England, I really believe that. I think the Virgin Prunes, because we were quite visual and quite full on there was a little bit of, “look at the Paddy-muckhead trying to compete with us.” There was a little bit of that, I’d go fuck off, BANG, slap them in the face almost. There was a little bit of that, “you shouldn’t be playing with Dada surrealism and Bowie and avant-garde, who do you think you are? You’re from Dublin, you’re fuckin’ muck.” There was a bit of that. My Bloody Valentine did go to Europe but then they went back to London, but they got a learning curve, they were ready. When they went back to London, it started happening for them.

NME, 13 November 1982. Image from nothingelseon.

I don’t want to sound arrogant but I found out really quickly that London was not going to be good to us and because we were so visually visceral — I mean we simulated oral sex and rape — [laughing] that was enough. We played a show in Brixton in November ’81 with The Birthday Party and someone who worked for Mary Whitehouse came along and we were banned. We couldn’t play Britain, even though we’d an album out in ’82 we didn’t play Britain again until ’83. We were banned for being sexually lewd, we had to submit the lyrics of what we were going to do. That was a signal, I tell you Paris and Holland and Belgium were much more exciting.

“How dare those Irish” — I’d say Michael O’Shea felt that, Donnelly probably felt it, no one that’s Irish didn’t feel it. I’d be a great conversation to have with Cathal — though I’m sure he’s bashed them all up with his IQ. Cathal — there’s a lot you could say about him — but he’s so learned. He was mentally and intelligently equipped and fuckin’ fighting. He got his phlegm out with the Fatima Mansions. He’s highly sharp — you don’t pick an argument with that do you?

Gavin Friday setlist. Image by Paul McDermott

© Paul McDermott 2020, All Rights Reserved

For Further Reading/Listening:

by Paul McDermott

The Goo - Issue 07 (Dec-Jan 2022)